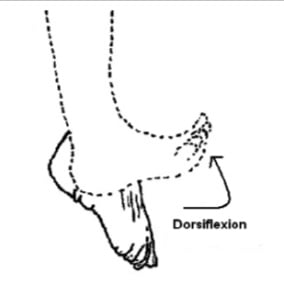

Hallux limitus is characterized by the restriction of dorsiflexion of the hallux (big toe of the lower limb) and degenerative changes within the first MTPJ (Metatarsophalangeal joint) whereas hallux rigidus is the complete absence of dorsiflexion at the first MTPJ, and develops at the endpoint of the same range of pathologies that cause hallux limitus.

The normal range of dorsiflexion at first MTPJ is 65-70 degrees. Hallux limitus describes a foot with less than 60 degrees of available dorsiflexion, whereas hallux rigidus has less than 5 degrees available dorsiflexion.

Hallux limitus is described as structural or functional hallux limitus. In structural hallux limitus, there is a limitation of dorsiflexion at the first MTPJ at all times, whereas, in functional hallux limitus, dorsiflexion is limited only when the foot is weight-bearing. In an unloaded foot with functional hallux limitus, the ROM at the first MTPJ appears relatively normal, but such a foot cannot function normally during gait.

ICD-10 FOR HALLUX LIMITUS:

- M20.20- Hallux limitus, unspecified foot

- M20.21- Hallux limitus, right foot

- M20.22- Hallux limitus, left foot

Etiology of hallux limitus/rigidus

It is a chronic degenerative condition that develops over time, in association with intrinsic (within the lower limb and foot) as well as extrinsic factors (e.g., systemic diseases).

Intrinsic factors:

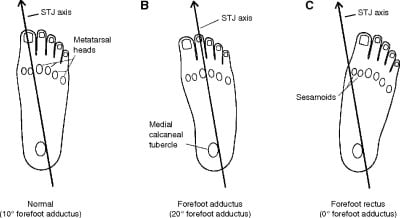

- FOOT SHAPE: The rectus foot (where the metatarsus adductus angle is <15 degrees) is more prone to develop hallux limitus.

- BIOMECHANICAL FACTORS: These include ankle equinus, flexible or rigid pes Plano valgus, flexible or rigid forefoot varus, dorsiflexion of the first ray, a hypermobile first ray, flexor plate immobility, plantar soft tissue contracture, and functional hallux limitus also.

- STRUCTURAL ANOMALIES: Anomalies within the lower limb that predispose to compensatory excessive foot pronation include external tibial torsion, tibial varum, genu valgum/varum/recurvatum, femoral retroversion, leg-length discrepancy, and also a wide-based gait. In addition to biomechanical factors, structural anomalies also lead to hallux limitus.

- Relatively long first toe or long first metatarsal also leads to hallux limitus.

- TRAUMA: such as damage to the articular cartilage at the first MTPJ, soft tissue tears, and sprains of the soft tissues around the first MTPJ.

Extrinsic factors:

- Inflammatory joint diseases within the foot such as rheumatoid arthritis, gout affecting the first MTPJ, and sesamoid degeneration.

- Occupations that require repeated and constantly forced dorsiflexion of the hallux at the first MTPJ may also lead to hallux rigidus.

- PELVIC NUTATIONS: Postural changes may cause pelvic tilt so that the pelvis tilts anteriorly (pelvic nutation), or posteriorly (pelvic counternutation). Pelvic nutation is especially associated with hallux rigidus due to its proximal effects (thoracic kyphosis, lumbar lordosis, internal rotation of the femur at the hip joint, internal rotation of the tibia at the knee joint, and whole foot pronation throughout the gait).

- Since excessive flexibility of the shoe forefoot increases the potential for hyperdorsiflexion of the hallux MTPJ. For this reason, this type of shoes should be avoided. Existing hallux limitus/rigidus become more symptomatic with certain shoe styles, such as high-heeled shoes, shoes with a thin sole, or a narrow toe box.

Classification of hallux limitus

| STAGE CRITERIA | CHARACTERISTIC FEATURES |

| GRADE 1 (functional hallux limitus) Available dorsiflexion at the first MTPJ – 60 degrees. | Functional limitation of dorsiflexion at the first MTPJ: > Hypermobility of the first ray > No marked joint deterioration > No sesamoid involvement > First MTPJ dorsiflexion may be near normal in the non-weight-bearing foot > First MTPJ area is usually painful under load |

| GRADE 2 (mild structural hallux limitus) Available dorsiflexion at the first MTPJ – 35-55 degrees. | Structural limitation of dorsiflexion at the first MTPJ: > Joint deterioration occurs > Narrowing of the first MTPJ > Moderate osteophytes at the first MTP area > Sesamoid hypertrophy > Pain in the first MTPJ area on movement and after exercise > Reduced dorsiflexion at the first MTPJ in both loaded and unloaded feet > Possible crepitus at the first MTPJ. > Reduced heel lift |

| GRADE 3 (moderate structural hallux limitus) Available dorsiflexion at the first MTPJ-15-30 degrees. | Structural loss of dorsiflexion at the first MTPJ: > Marked joint deterioration with severe loss of MTPJ space > Reduced height of the medial longitudinal arch > Decrease in calcaneal angulation > Marked reduction on heel lift > Crepitus with any movement of the first MTPJ > Dorsiflexion at the first MTPJ is severely reduced or absent |

| GRADE 4 (severe hallux rigidus) Available dorsiflexion at the first MTPJ- <15 degrees | Virtual or actual immobility of the first MTPJ: > Joint obliteration or ankylosis > Increase in the depth of the first MTPJ complex due to osteophytosis > Absent heel lift |

Clinical features of hallux limitus

Patients with hallux rigidus complain of dorsal pain, swelling, and stiffness localized to the hallux MTP Joint, especially after walking or exercising. There may be a history of minor injury. There may also be joint crepitus on movement. The sitting examination may reveal decreased ROM in dorsiflexion and, to a lesser degree, in plantar flexion. ROM becomes more and more painful as the condition advances. Forced dorsiflexion reveals an abrupt dorsal bony block associated with pain. In addition, forced plantar flexion produces pain as the dorsal capsule and the extensor hallucis longus tendon are stretched across the dorsal osteophyte. In this case, the dorsal osteophyte is easily palpable and typically exquisitely tender.

Diagnosis and differential diagnosis

The diagnosis of hallux limitus and hallux rigidus is made from the clinical signs and the patient’s symptoms and confirmed by radiography.

Standard radiographic evaluation includes AP, oblique, and lateral views of the weight-bearing foot.

| DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS | SIGNIFICANT FINDINGS |

| Hallux rigidus | Chronic condition Limited dorsiflexion Dorsal osteophytes on the lateral radiograph |

| Hallux valgus (bunion) | Chronic condition Lateral deviation of the great toe Tender medial eminence (not dorsal spur) Increased hallux valgus angle on the radiograph |

| Hallux arthrosis (arthritis first MTPJ) | Chronic condition Painful and limited ROM Loss of entire joint space on the radiograph |

| Gout | Acute severe pain Tenderness, erythema joint irritability localized to first MTP Elevated uric acid Sodium urate crystals |

TREATMENT

Treatment of the hallux limitus/rigidus is based on the symptoms. Acute exacerbations are treated with the RICE (rest, ice, compression, and elevation) method, followed by a gentle ROM program and protected weight-bearing. Chronic conditions are treated with a ROM program and protected weight-bearing. The hallux MTPJ is supported by shoe modifications (e.g., rocker-bottom shoe).

The joint is also protected by reducing activity levels, increasing rest intervals and duration, and avoiding excessively firm play surfaces.

NSAIDs and cold therapy are used to reduce swelling and inflammation. Occasionally, injection of corticosteroid into the MTPJ is used as adjunctive therapy.

Operative treatment is indicated for symptoms that fail to respond to a reasonable period of well-supervised conservative management. Hallux MTP debridement and exostectomy are standard treatments for hallux rigidus.

Non-operative treatment:

ACUTE PHASE (DAYS 0-6)

- Rest, ice bath, contrast bath, whirlpools, and ultrasound for pain, inflammation, and joint stiffness.

- Joint mobilization, followed by gentle passive and active ROM.

- Isometrics around the MTP joint as pain allows.

- The isolated plantar fascia stretches with a can or golf ball.

- Cross-training activities, such as water activities and cycling, for aerobic fitness.

- Protective taping and shoe modifications for continued weight-bearing activities.

SUBACUTE PHASE (WEEKS 1-6)

- Modalities to decrease inflammation as well as joint stiffness.

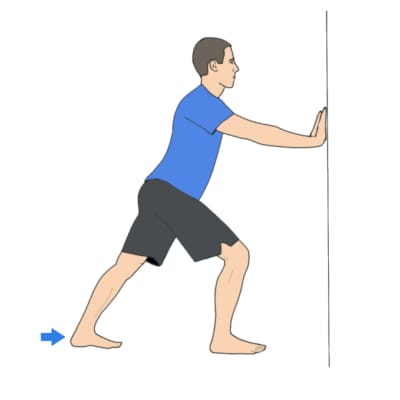

- Plantar fascia stretching as above,

- Gastrocnemius stretching

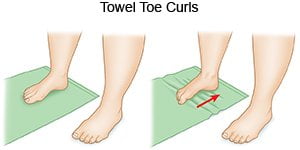

- Towel scrunches

- Toe pick-up activities

- Toe and ankle dorsiflexion.

- Isolated toe dorsiflexion

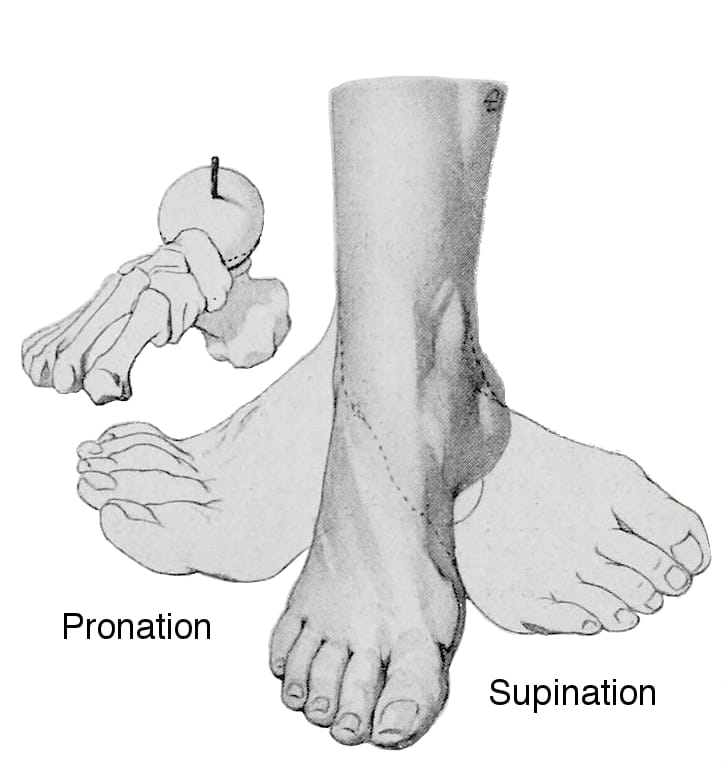

- Supination-pronation.

- Balance activities on the balance board.

RETURN TO SPORTS PHASE (WEEK 7)

- Continued use of protective inserts

- Continued ROM as well as strengthening exercises

- Running within the limits of a pain-free schedule

- Monitored plyometrics with progression to difficulty.

Conclusion:

Today, in this article we have discussed hallux limitus and rigidus along with their classification, clinical features, diagnosis, and treatment. We have also discussed non-operative treatment in detail. If you have any queries related to it, then you can mail your queries to physiociti@gmail.com.

ALL THE BEST!